A Night of Happenstance

Lee Rosy’s tea room, 17 Broad Street, Nottingham, NG1 3AJ

Saturday 26 November, 7.30pm

Entrance £4/£3 (concs)

Six Happenstance poets, from across the Midlands, Scotland, and as far away as Spain, will be gathering for a reading downstairs at Lee Rosy’s in Nottingham on 26 November 2011, from 7.30pm. The poets are Helena Nelson (also editor of Happenstance Press), Ross Kightly, Marilyn Ricci, Robin Vaughan-Williams, DA Prince, and Matthew Stewart, who will be in the country to launch his new pamphlet, Inventing Truth.

Happenstance is an independent poetry press based in Scotland that publishes poets from all over the UK. It specialises in pamphlets, and in 2010 won the Michael Marks Award for Poetry Pamphlets for publishers. Ali Smith, one of the judges, commented, ‘HappenStance proved outstanding in the elegance, thoughtfulness and clarity of their design, and the infectious interaction, open-mindedness and energy of their publishing ethos’.

Happenstance also produces Sphinx, an indispensable source of poetry pamphlet reviews.

Happenstance also produces Sphinx, an indispensable source of poetry pamphlet reviews.

Lee Rosy’s is a tea room and café in Nottingham city centre’s Hockley district, opposite the Broadway cinema.

About the Poets

Helena Nelson

Helena Nelson is editor and founder of HappenStance Press, which specialises in poetry pamphlets. Her most recent poetry collection in her own right is Plot and Counter-Plot, (Shoestring Press). Helena is also this year’s judge on the Nottingham Open Poetry Competition, and will be attending the adjudication at 2.45pm on the same day (Mechanics Institute, 3 North Sherwood Street, NG1 4AX).

Helena Nelson is editor and founder of HappenStance Press, which specialises in poetry pamphlets. Her most recent poetry collection in her own right is Plot and Counter-Plot, (Shoestring Press). Helena is also this year’s judge on the Nottingham Open Poetry Competition, and will be attending the adjudication at 2.45pm on the same day (Mechanics Institute, 3 North Sherwood Street, NG1 4AX).

DA Prince

DA Prince started out with light verse and political satire, but gradually found herself shifting into the realms of what might be called ‘proper’ poetry (the sort that poetic/moody poets write). After having three pamphlets in print, her first full-length collection Nearly the Happy Hour came out in 2008 from HappenStance. More about DA Prince is available on PoetryPF.

DA Prince started out with light verse and political satire, but gradually found herself shifting into the realms of what might be called ‘proper’ poetry (the sort that poetic/moody poets write). After having three pamphlets in print, her first full-length collection Nearly the Happy Hour came out in 2008 from HappenStance. More about DA Prince is available on PoetryPF.

Ross Kightly

Born in Melbourne in 1945, Ross Kightly spent many years teaching in Victoria, Croydon, ILEA, Lucca (Italy), and then Yorkshire. Since recovering from viral encaphalitis in 2007 Ross has devoted himself to the heroic task of becoming the World’s Most Prolific Poetaster by setting himself ridiculous output targets, such as 7,457 poems for 2011 (which works out at over 20 a day). Gnome Balcony was published in 2011.

Born in Melbourne in 1945, Ross Kightly spent many years teaching in Victoria, Croydon, ILEA, Lucca (Italy), and then Yorkshire. Since recovering from viral encaphalitis in 2007 Ross has devoted himself to the heroic task of becoming the World’s Most Prolific Poetaster by setting himself ridiculous output targets, such as 7,457 poems for 2011 (which works out at over 20 a day). Gnome Balcony was published in 2011.

Marilyn Ricci

Marilyn Ricci lives in Leicestershire. Her poems have appeared in anthologies and been widely published in magazines including Other Poetry, Orbis, The Rialto and Smiths Knoll. Her first pamphlet Rebuilding a Number 39 was published by Happenstance Press in 2008.

Marilyn Ricci lives in Leicestershire. Her poems have appeared in anthologies and been widely published in magazines including Other Poetry, Orbis, The Rialto and Smiths Knoll. Her first pamphlet Rebuilding a Number 39 was published by Happenstance Press in 2008.

Matthew Stewart

Matthew Stewart was born in Farnham, Surrey, in 1973, but has lived in Extremadura, Spain, for the past fifteen years, where he works for a local winery. His poems have been widely published in UK magazines and he blogs at Rogue Strands. Inventing Truth, his Happenstance publication, ‘is a remarkable collection of pithy poems that open up to panoramas of love, family, regret and longing, and linger, flourishing in the mind long after reading’ (Richie McCaffery).

Matthew Stewart was born in Farnham, Surrey, in 1973, but has lived in Extremadura, Spain, for the past fifteen years, where he works for a local winery. His poems have been widely published in UK magazines and he blogs at Rogue Strands. Inventing Truth, his Happenstance publication, ‘is a remarkable collection of pithy poems that open up to panoramas of love, family, regret and longing, and linger, flourishing in the mind long after reading’ (Richie McCaffery).

Robin Vaughan-Williams

After many years in Sheffield, where he ran the Spoken Word Antics monthly night and radio show, Robin Vaughan-Williams moved to Nottingham via Iceland in 2010. He is Development Director at Nottingham Writers’ Studio, author of The Manager, and also a live literature producer. Some of his projects are shown at zeroquality.net.

After many years in Sheffield, where he ran the Spoken Word Antics monthly night and radio show, Robin Vaughan-Williams moved to Nottingham via Iceland in 2010. He is Development Director at Nottingham Writers’ Studio, author of The Manager, and also a live literature producer. Some of his projects are shown at zeroquality.net.

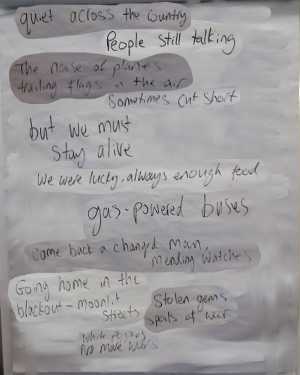

Last week we had an inspiring session working on a collaborative poem to do with war. In the past, some of the best sessions I’ve facilitated have been the most spontaneous ones, which haven’t relied much on preparation and where the participants have had a lot of input into the content of the class or workshop. This was one of those sessions.

Last week we had an inspiring session working on a collaborative poem to do with war. In the past, some of the best sessions I’ve facilitated have been the most spontaneous ones, which haven’t relied much on preparation and where the participants have had a lot of input into the content of the class or workshop. This was one of those sessions. Happenstance also produces Sphinx, an indispensable source of poetry pamphlet reviews.

Happenstance also produces Sphinx, an indispensable source of poetry pamphlet reviews.

After many years in Sheffield, where he ran the Spoken Word Antics monthly night and radio show,

After many years in Sheffield, where he ran the Spoken Word Antics monthly night and radio show,